Last post I attempted to explain, in no uncertain terms, why taking a Guard in the first round makes little sense (especially in the top half of the first round). However, I get the sense that many people remain unconvinced. Today, I’ll take a slightly different look at it to see if I can sway the remaining holdouts. I apologize for the repetition in subject-matter, but this is an EXTREMELY important topic, as it goes to the heart of Optimal Draft Strategy.

First, I want you to ask yourselves if you agree with the following statement:

GMs should, in general, take the Best Player Available (“BPA”) with every draft pick.

I’m guessing most readers here would back that strategy, and I certainly do. HOWEVER, it is not enough to just endorse that statement and use it as the basis for a draft strategy. First, you must definite exactly what BPA means.

Here is where I am seeing some confusion and where I believe there is a big disagreement. The people calling for taking Warmack high in the draft (forget about the Eagles for a moment, I’m speaking in broader terms), are using BPA as support. The problem is that, in their BPA definition, they do not seem to be adjusting for positional value, which is a MASSIVE mistake.

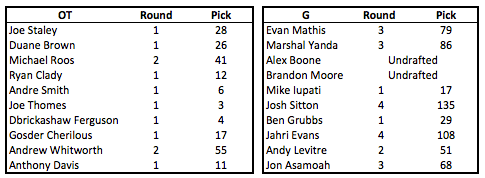

Rather than attempting to explain why with a rational argument (for that see my last post), I’ll try to illustrate it. Here are the top ten OTs and Gs from this past season, according to Pro Football Focus. They are listed in order, with their original draft pick included.

There are two big takeaways from this chart. First, look at the draft picks.

I know I’ve said this repeatedly, but if you want an “elite” OT, you have to take him in the first round. The same clearly does not hold for the Guard position. This provides a clearer illustration of the opportunity cost argument I made last week. There are really only two ways to get an elite OT in the NFL, draft him or sign him in FA. (I know we traded for Peters, but that’s a RARE exception). Additionally, signing an elite OT in FA requires a huge contract. Therefore, the BEST way to add a top OT to your team is to draft him in the first round. Choosing a G means you are forgoing that opportunity.

The second point I want to highlight from the chart above gets at positional value. Again, I want you to answer a question:

All other things being equal, would you rather trade Anthony Davis for Evan Mathis (or any other top Guard) or vice-versa?

I’m a big Mathis fan, but that’s a no-brainer. Clearly most of the league agrees as well, hence the salary differences between OTs and Gs.

Assuming you agree, that means the #10 OT is worth more than the #1 G.

How about Brandon Albert versus Evan Mathis?

This one probably creates a bit more disagreement, but my guess is, on the whole, people would take Albert, who ranked as the 25th best OT according to Pro Football Focus.

Regardless, clearly there is a discrepancy in value between OTs and Gs. Also, while I’ve focused on Gs and OTs, the same analysis can (and must be) done with all positions, and then incorporated into each team’s prospect rankings. To not account for this is a huge mistake and one that appears is made by a lot of the writers who support taking a G high in the draft under a flawed concept of BPA.

To make sure I’m being clear: This should be incorporated into the “tiered” rankings I advocated previously. So it is theoretically possible for a G to be the best choice with a top 15 pick, but it would require an amazing G prospect that can overcome the positional value difference to make it to the top 1 or 2 tiers, as well as every other player (from positions of greater value) within the same prospect tier being taken before said top 15 pick.

Hopefully this has convinced a few more of you, or at least provided a clearer explanation of what I was getting at last week. This isn’t exactly Eagles-specific, because I don’t think there’s any way they take Warmack at #4, but it applies to any team with a top 15 pick.

Lastly, I’ll leave you with an analogy. A frequent defense of G picks (and OL picks in general) in the first round has been that they are “safer”. In general, that is true, as our strategy chart showed. However, this is only one half of the equation. As anyone in finance knows, evaluation is always a question of risk vs. REWARD. To look at one side and ignore the other is a recipe for sub-optimal decision-making.

For example, given the choice between to raffles, and ignoring an external factors, which would you rather enter:

A) 60% chance of winning $100.

B) 75% chance of winning $75.

While the odds of success for raffle B are significantly higher, the correct answer (in a vacuum) is A, since the expected payout is greater. It’s impossible to apply such specific values to players, but it’s a useful exercise nonetheless. Here, imagine a DE as raffle A and an OL as raffle B. To take the OL just because he offers less risk (25% chance of miss versus 40%) would clearly be a poor decision.