Time for another guest post from Jared. For those of you who don’t know, Jared is my brother. He’s also a U of Chicago MBA and a two-time Jeopardy! champion. You can follow him @jaredscohen or see the original of this post at his site, linked here. Now, his words:

Last year I put together some analysis of NFL kick returns. I was really motivated by one big question – Why do teams return kicks?

Initially, I wondered if returning kicks was even the optimal decision for teams trying to win football games. I wondered if the risks of turnovers and poor field position meant teams really should prefer a touchback to bringing the ball out of the end zone.

As a brief review, that’s not the case. Returning kicks is, on average, better for scoring points than taking a knee in the end zone as the returns leave your team with better field position. If you look at it in terms of expected points generated on kick returns vs. generated on touchbacks – the distinction is clear: (Note: this analysis relies on the concept of expected points based on field position – which I’ll assume readers have already seen and grasped)

This data comes from the first 16 weeks of this NFL season, over 2400 kicks. It’s also consistent with last year’s data.

So returning kicks is good, but think about why it’s a good idea. Although it presents better average field position, the average return nets only about four yards of position (and only two yards if the ball is brought out of the end zone relative to a risk-free touchback).

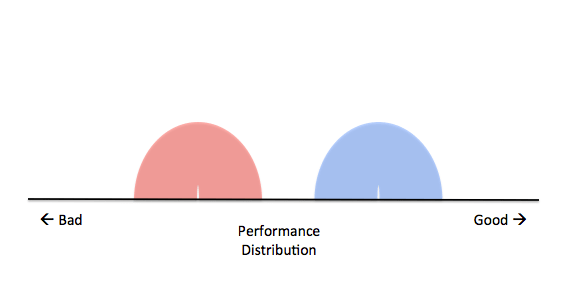

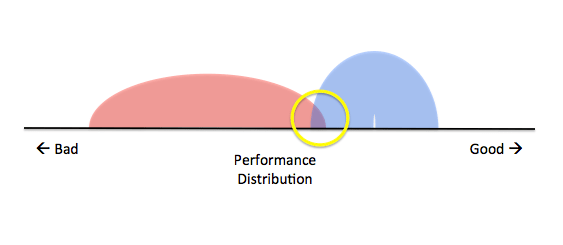

Linking back to material my brother has posted – the upside is directly tied to variance. Returning kicks is much more of a high-variance strategy.

Below – is an illustration of all returned kicks through Week 16 this year. The histogram shows the distribution of expected points.

You see the giant spike between 0.3-.04 which equates to a return between the 18 and 22 yard lines, that’s the most typical result (remember a touchback is worth 0.34 expected points). But there’s also an extremely long tail of positive performance, and these outliers can be worth a lot more (even a touchdown). Those outliers are what make kick returns worth the risks (injury, turnover), which is exactly what we mean when we talk about high-variance strategies.

A touchback has zero variance. That result is predictable and constant. But a return, that could be a whole bunch of possibilities.

OK – so let’s take the idea that returning kicks instead of taking touchbacks is a high-variance strategy as a hypothesis. Now, if that’s true, we would expect to see a couple different trends in the data. Generally, we would expect less talented teams to return kicks MORE often than their better opponents. Weaker teams should be pursuing higher variance plays in an attempt to pick up ground on those other (stronger) squads. In an example – you’d expect the Jaguars to try everything to beat the Broncos because Denver is extremely talented and playing a conventional game will leave the Jaguars at a big disadvantage. That could mean any number of things, more shots downfield, 4th down conversion attempts, surprise onside kicks, and we could expect – more kick returns.

So…is that something we actually observe in the data? Are weaker teams pursuing higher variance strategies in the form of more frequent kicks?

To test this, I went back and looked at my favorite kickoff metric – percentage of touchback eligible kicks returned. This counts the number of kicks that were returned out of the end zone as a proportion of the total number of kicks fielded in the end zone. Obviously – teams will return all kicks fielded short of the end zone, so we need to exclude these. The real decision point is whether or not teams bring balls out of the end zone – this is our true high variance strategic choice.

The data set it built off of play-by-play information, which is the best I can get. Unfortunately, there are a large number of touchback kicks where distance is not recorded and it isn’t specified whether the kick was fielded or kicked out of the end zone. After some initial eyeballing I’m confident these are kicks out the back of the end zone (Matt Prater of the Broncos had a lot of them as an example). So our set of kicks is a little smaller than you might expect. But there are still 950 kicks in our sample.

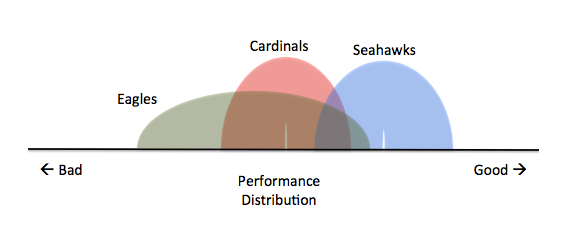

Then, I took all the NFL teams and split them into three performance tiers based on point differential. Teams with the highest point differential are members of the first tier, teams with the worst scoring differential are in the third tier. Below are the teams and their tier positions.

You can see the usual suspects in both the first and third tiers. And to me, this is where we’d expect to see the biggest change. These third tier teams – they have to do MORE to compete against first tier teams. Alternatively, first tier teams, one might argue, don’t need to take additional risk by sending their return man out of the end zone. If we look at touchback eligible kickoff return percentage across the different matchups – we can see if there’s any difference in the way teams behave. Do third tier teams return more kicks when they face off against first tier teams? Do first tier teams (who don’t need to pursue high-variance strategies) return fewer kicks?

Hmm…there’s almost no difference in return % whether the worst teams are facing other crappy teams or the best teams. That seems a little odd…as we had guessed the worse teams SHOULD be returning more kicks when they face better teams. This indicates that this doesn’t happen.

It’s also not a result of sample size, as most of these cells are large enough (80-120 observations).

As another check, I looked at touchback eligible return percentage relative to specific team talent (via point differential) on a team-by-team basis. I did this to see if there were any teams that really seemed to be demonstrating aggressive tactics at the individual level.

Again, this doesn’t appear to support our thinking that poor teams are pursuing higher variance strategies by returning more kicks. At best, it’s inconclusive. There are a couple of teams, like the Vikings, who really push the envelope – but there’s not a major correlation between team talent and return percentage (correlation is roughly -0.15)

Strange, but maybe identifying high-variance strategies before the game starts and following them blindly isn’t really what coaches of less-talented teams spend time on. Is there another way we can test our hypothesis?

Another theory is that if teams aren’t determining to return more kicks as part of pre-game strategy, maybe it’s something they pursue once they fall behind on the scoreboard. This wouldn’t even have to be exclusive to poor performing teams – any team that’s fallen behind might be more likely to run back kicks to try to break a big play to help catch up. What if we examine touchback eligible return percentage by in-game score differential?

The chart below illustrates the return percentage across a set of different score bands, ranging from down by more than 14 points to ahead by more than 14 points.

Again – there doesn’t seem to be any real connection between the scoreboard and aggressive kick return tactics. A team down by more than two touchdowns is just as likely to return a kick out of the end zone as one who is tied. If a kick return out of the end zone is indeed an aggressive play with a higher reward – teams don’t appear to be pursuing it MORE when they need to make up ground or LESS when they have a large lead. (As an aside, I absolutely cannot explain why having a small lead seems connected to a dramatic drop off in returns. I’ll chalk that up to some data wonkiness unless someone has a great insight there.)

But the broader concern remains. Shouldn’t teams which are behind or less talented need to take more chances to win? Why aren’t they doing that and bringing kicks out of the end zone?

My initial guess, though I’d welcome other speculation, is that teams the organizational structure of coaching almost inhibits something like that from happening. This comes with the obvious caveat that I’ve never coached in the NFL (so sure, Bill Belichick or someone else can dismiss all this out of hand as mom’s basement musings – but screw them). But if you’re the special teams coach of an NFL team – your work includes a thorough evaluation of your special teams and your upcoming opponent. All that work and planning becomes a little less valuable if a head coach just says – ‘Hey, I think we should return any kick we get in the end zone’

If the special teams coach is to maintain any kind of control over what his squad does – a simplistic rule like ‘run them out when we’re behind’ may not be sophisticated enough to justify all that pre-work and planning.

But that’s just a thought, based on the idea that coaches know their teams and customize approaches based on their own teams’ skills and the matchup with the opponent. Of course, when you actually look at the data, teams don’t really appear to be all that successful in managing their return game. Below is an illustration of touchback eligible return percentage, but this time charted against the average return position (i.e., return ability).

While we’d expect to see some correlation here – to show that teams with good return games return more kicks and teams with poor return teams take more touchbacks – that’s only true to the degree of a 0.2 correlation.

Some teams seem to get it – the Bills are really bad in the return game, but they rarely return kicks out of the end zone (on a relative basis – still over 50%). At the other extreme are the Vikings. The have Cordarrelle Patterson and, as such, they return kicks out of the end zone over 95% of the time!!!

On the flip side, look at Washington and St. Louis, teams with mediocre return units that run kicks out of the end zone 90% of the time. The Chiefs and Ravens seem odd as well – teams with great performance who could stand to run some more back. Now, maybe the Redskins are pursuing a high variance strategy, and maybe the Chiefs a more conservative one, but the overall results remain inconclusive.

At the end of the day, I come back to the idea of coaches and control over their special teams. For any team to read any of this and think about employing a ‘high-variance’ strategy – it really requires an admission of the role of chance in the outcome of a football game. Running every kick out of the end zone is a strategy based on the concept of inherent variability in outcome. Some returns may get stuffed, and others may go for big returns, but you can’t be sure when one or the other will happen. That view, to me, is fundamentally opposite the idea that with the right scheme and flawless execution – you can create the optimal outcome.

One of those ways of thinking supports the coach as the ultimate authority, while the other incorporates more probabilistic thinking. That gap is why I think we haven’t seen any patterns to support our hypothesis, and no clear evidence of high-variance kick return strategy consistently employed in today’s game.