Patrick Causey, on Twitter @pcausey3

In case you haven’t noticed, the Eagles have several sizeable holes on the offensive side of the football. The only reliable receiver on the roster to date is Jordan Matthews, while the Eagles’ offensive line faces questions thanks to Jason Peters losing his battle with Father Time and Lane Johnson losing his battle with integrity. In a league predicated on protecting the quarterback and passing the football, that could spell trouble for the Eagles.

But the talent at tight end and running back could mitigate some of these concerns. Zach Ertz, Brent Celek and Trey Burton give the Eagles one of the deepest and most versatile tight end units in the league, and their presence should not only bolster the team’s receiving options but also help ameliorate the offensive line issues. And the oft-overlooked Darren Sproles could become a revelation in this offense, reassuming the Danny Woodhead-type role he practicaly invented in New Orleans.

These players could have helped the team last year, but Chip Kelly’s religious adherence to the 11 personnel — three wide receivers, one tight end, and one running back — meant more Miles Austin and Riley Cooper, and less Ertz, Celek, Burton, and Sproles. Of all the frustrating things about Kelly’s tenure (and there were many), his preference for allowing scheme to dictate playing time — instead of talent — was at the top of my list.

I would expect the opposite to occur under Doug Pederson, with tight end and running back being key cogs on this offense, especially in the passing game. Look no further than Pederson’s mentor, Andy Reid, to get an idea of how involved they could become. Dating back to 2000, Andy Reid coached teams have had a running back or tight end rank in the top two on the team in catches every single year (all numbers courtesy of Pro-Football-Reference.com):

- 2000: 1st: Chad Lewis, TE, 69 catches, 735 yards, 3 touchdowns

- 2001: 1st: Duce Staley, RB, 63 catches, 626 yards, 2 touchdowns

- 2003: 2nd: Brian Westbrook, RB, 37 catches, 332 yards, 4 touchdowns

- 2004: 2nd: Brian Westbrook, RB, 73 catches, 703 yards, 6 touchdowns

- 2005: 1st: Brian Westbrook, RB, 61 catches, 616 yards, 4 touchdowns (TE LJ Smith was tied for first with 61 catches as well)

- 2006: 1st: Brian Westbrook, 77 catches, 699 yards, 4 touchdowns (LJ Smith ranked 2nd)

- 2007: 1st: Brian Westbrook, 90 catches, 771 yards, 5 touchdowns

- 2008: 2nd: Brian Westbrook: 54 catches, 402 yards, 5 touchdowns

- 2009: 1st: Brent Celek: 76 catches, 971 yards, 8 touchdowns

- 2010: 1st: LeSean McCoy: 78 catches, 592 yards, 2 touchdowns

- 2011: 2nd: Brent Celek, 62 catches, 811 yards, 5 touchdowns

- 2012: 2nd: Brent Celek: 57 catches, 684 yards, 1 touchdown (LeSean McCoy ranked third)

- 2013 (Kansas City): 1st: Jamaal Charles: 70 catches, 693 yards, 7 touchdowns

- 2014: 1st: Travis Kelce: 67 catches, 862 yards, 5 touchdowns

- 2015: 2nd: Travis Kelce: 72 catches, 875 yards, 5 touchdowns

That’s 15 years of heavily involving the running backs and tight ends in the passing game. That should be welcomed news for a team that — as Brent laid out earlier — have yet to see a good return on their investment in the wide receiver position.

More Tight Ends Please: 12 and 13 Personnel and the Y-Iso

Both Pederson and offensive coordinator Frank Reich recently praised the tight ends as a strength of the Eagles’ offense, hinting that they will have an expanded role this year. And if Pederson’s time at Kansas City is any indication — where they routinely relied on 12 (two tight end sets) and 13 (three tight ends) personnel groups — he will follow through on that promise.

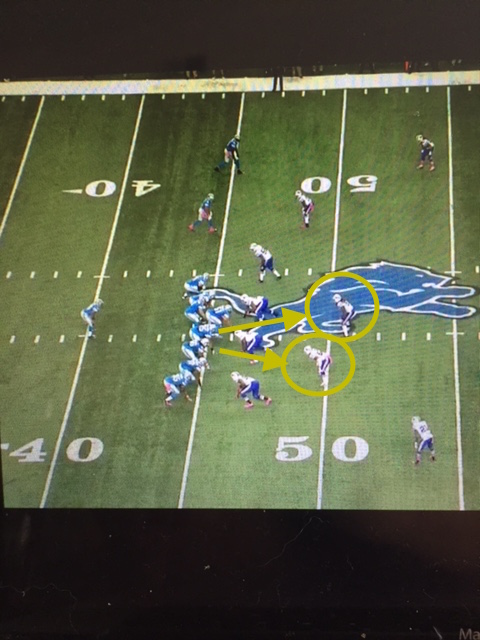

We saw this on the first drive of the first preseason game, when the Eagles lined up three tight ends in a power run formation deep in the red zone. It was a jarring site to behold after watching three straight years of the Eagles foolishly running exclusively out of the shotgun:

The benefits of using multiple tight ends in the run game are obvious. Tight ends are typically larger, and better blockers than receivers, so it helps create better lanes for a running back to exploit. The extra reinforcements will be especially important during the first 10 weeks of the season when Lane Johnson is suspended.

The extra blockers should also help in the passing game. Last season, the Chiefs had issues all along their offensive line, but especially at the guard position. The Chiefs combated those concerns by keeping in extra blockers to buy Alex Smith more time to attack the defense down field.

Here, the Chiefs line up in 12 personnel, with Kelce and Demetrius Harris as the two tight ends. Kelce gets open and scores an easy 42-yard touchdown, but the play was made possible by Harris and center Mitch Morse double teaming J.J. Watt.

Given Celek’s strength as a blocker, I would expect to see him giving help to Allen Barbre often this season, easing the blow of losing Johnson to suspension. It’s a smart use of the players at your disposal, but was rarely something that Kelly did last season.

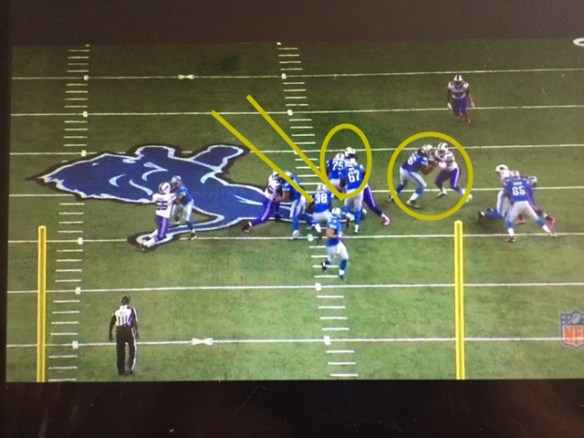

Extra tight ends has the secondary benefit of setting up the play-action pass, which is one of the few areas that Sam Bradford performed at an elite level last year. Indeed, if you continue to run the ball down a defense’s throat with the 12 or 13 personnel, they will counter by stacking 8 men in the box to stop the run. That creates easy pickings for the play action pass over the top, something the Chiefs used successfully last season with Travis Kelce:

The Chiefs routinely exploited the matchup problems Kelce’s size, speed and route running ability presented. He was too big for safeties, too fast for opposing linebackers, and that mismatch was especially problematic in the redzone. But it didn’t just occur by happenstance. Pederson/Reid purposefully designed plays to get Kelce in favorable matchups in the end zone.

Watch this play design. The Chiefs are using their 13 personnel, with three tight ends lined up at the top of the screen. Kelce is on the outside and is going to run a post pattern in the end zone. But watch as Harris and James O’Shaughnessy run staggered post and in routes at 5 and 10 yard intervals, respectively. They occupy the middle linebackers and safeties, freeing up Kelce for a one-on-one matchup on the outside.

Zach Ertz presents a similar matchup problem for opposing defenses, and flashed big time talent down the stretch last year catching 30 passes over the final three games of the season. But Kelly rarely designed plays for his best players, including Ertz. Kelly believed that he could scheme players open and expected his quarterback to find the open target, regardless of who it was. I don’t expect that to be a problem this year. Ertz should quickly become Sam Bradford’s favorite red zone target, with Pederson designing plays like the one above to get Ertz in favorable matchups.

Pederson will also look to generate favorable matchups by the location in which tight ends are placed on the field. The Chiefs routinely spread tight ends out wide against cornerbacks, which is like posting up a power forward on a shooting guard. It just isn’t a fair matchup for the defense.

The final, and perhaps most significant way we will see the tight ends get more involved is through the “Y-Iso” formation. The formation consists of trip wide receivers on one side of the formation and a tight end lined up in the Y receiver spot on the other side. Bill Belichick reintroduced this to the league a few years back, unleashing Rob Gronkowski on unsuspecting defensive backs in a hilariously unfair mismatch.The Chiefs — and many other teams in the NFL — followed the Patriots lead and have used the Y-Iso formation to great success.

According to Pro Football Focus, the amount of snaps in the Y-Iso formation has more than doubled since 2011, rising from 1,569 to 3,503 in 2015. The Chiefs and San Diego — were Frank Reich was the offensive coordinator — ranked fourth and fifth in the league in Y-Iso snaps, respectively.

In week 16 last year against the Browns, the Chiefs lined up Kelce in the Y-Iso formation at the bottom of the screen, while three receivers were split out on the opposite side of the field. Kelce is matched up one-on-one with Pro Bowl cornerback Joe Haden, who has safety help over the top. That is, until Jeremy Maclin occupies the safety just long enough to free Kelce for the easy score.

If you watch Maclin closely on this play, I am not entirely sure he is even looking to catch the ball. It looks like he ran his route solely for the purpose of occupying the safety so that Kelce could get free. Regardless, that is just a great play design by the Chiefs, and another example of how Ertz, Celek and Burton could be used this season.

The Return of Darren Sproles

I’ve already laid out why I think Mathews could be an effective running back, but even at the tender age of 34, Sproles could finally become the dynamic threat in the passing game we all envisioned when he was acquired from the Saints. Sproles was Danny Woodhead before Danny Woodhead, and that fact was not lost on Frank Reich (who was Woodhead’s offensive coordinator last year in San Diego):

When Sproles was acquired by the Eagles in the 2014 offseason, he was coming off back to back seasons of being targeted over 100 times. During those two years, Sproles caught a combined 161 passes for 1,377 yards, and 14 touchdowns. He was a matchup nightmare and one of Drew Brees’ favorite targets.

But in Sproles’ three seasons with the Eagles, he has caught only 166 passes for 1,379 yards and 3 touchdowns. Kelly often praised Sproles dynamic ability, but failed to consistently use him.

If Frank Reich’s use of Danny Woodhead in San Diego is any indication, I wouldn’t expect that to continue. In 2013 and 2015 (Woodhead missed most of 2014 due to injury), Woodhead combined for 156 catches, 1,360 yards and 12 touchdowns in the air. Woodhead was Phillip River’s safety valve and one of his favorite red zone targets. And despite being viewed as only a third down back, Woodhead had 597 offensive snaps last season according to FootballOutsiders.com, which ranked 13th in the league among running backs and was 201 more snaps than Melvin Gordon, who was supposedly the starter.

Comparatively, Sproles had 393 offensive snaps last year under Chip Kelly, which ranked 35th in the league and placed him behind the likes of Theo Riddick and Isaiah Crowell. Even if Sproles isn’t used as often as Woodhead was last year — and indeed, I would be surprised if he was given his age — I expect to see smarter play designs aimed at getting the ball in Sproles hands.

Notice the play design here? It’s the Y-Iso formation we covered earlier. This play isn’t as important so much as what it does for setting up Woodhead to score on the next series, but play along for a minute. Ladarius Green is in the Y-Iso formation with Melvin Gordon lined up in the backfield on the same side of the field. Green breaks free on a crossing pattern and scoots in for the easy score.

On the very next drive down in the red zone, the Charges call the same Y-Iso formation, this time with Green on the opposite side of the field and with Woodhead in the backfield instead of Gordon. Having just been burned by Green for a touchdown, the Raiders defense doubles Green, leaving Woodhead wide open for an easy score.

This is a great play call from Frank Reich and an example of how an offensive coordinator can set up certain play calls during the course of a game. Reich knew the defense would recognize the formation and stick Green, and used that aggressiveness against them. Sub in Ertz and Sproles for Green and Woodhead — different players, but likely the same results.

The Chargers didn’t just target Woodhead out of the backfield, either. They did a great job moving Woodhead all over the field, splitting him out wide and lining him up in the slot. Against the Dolphins (where Woodhead scored 4 total touchdowns), Woodhead was able to spring free with a nifty out and up route for a score.

Later in the game, the Chargers again dialed up a play designed to spring Woodhead for an easy score. Woodhead is lined up out wide on the lower side of the field, while the Dolphins are in man coverage with a single high safety. The Chargers break Woodhead open by running a pick play on Woodhead’s man. That’s just easy money.

Over the last few years, I have been calling for the Eagles to use Sproles in a similar fashion. He is so difficult to cover in space given his precise route running and overall shiftiness. They rarely took advantage of that the last three seasons, but I expect to see Sproles (and perhaps Smallwood) get an opportunity to shine in the passing game this year.

I came into this season with serious reservations about the Eagles offense and their head coach, Doug Pederson. I still have those reservations, but digging into the film more gives me some hope that the offense will not be a total train wreck.

Both Pederson and Reich have a history of catering their scheme to their personnel, which is a nice contrast from the Chip Kelly experience. Given the Eagles holes at receiver and the potential issues along the offensive line, I expect to see the tight ends and Darren Sproles more heavily involved in the offense. It might not be the most prolific offense in the league, but it should be more effective and efficient than what we saw the last two years.