Yesterday I compared the FO win projections for every team against the O/U lines from online bookmaker Bovada.lv. I was light on analysis, so today I’ll focus more deeply on a few teams that carry the largest deviations. After writing the UNDER-rated section, it was apparent that this post needs two parts. So the OVER-rated teams will have to wait until tomorrow.

Reminder – The Bovada line isn’t meant to be a prediction, but in theory, should function as a measure of what the general (betting) public thinks of each team. So when the Bovada line is HIGHER than the FO projection, I’m calling that team OVERrated.

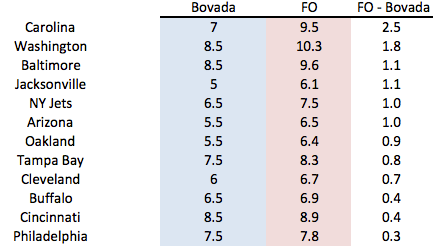

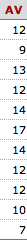

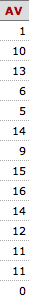

First, let’s look at the UNDER-rated teams. Here they are:

Above are all of the teams that have a higher FO projection than Bovada O/U. I’m going to focus on the teams with the largest differential, for obvious reasons.

Carolina

A difference of 2.5 wins is HUGE. If betting we legal (and if I had data on FO’s predictive accuracy), I’d be very tempted to take the over here, figuring that if the “true” value of the Panthers team is 2.5 wins above its O/U, then the team can suffer some bad luck and still hit the over. Why the big difference?

The Panthers won 7 games last year, the same number as the current 2013 O/U. That makes things fairly easy from a projection standpoint. All we need to do is answer: Why will the team be better this year than last?

The main factor in the FO projections (i think, I don’t now the formula) is the team’s 0-7 record in close games. Typically, that record in close games (<7 Points) is close to .500. Just going 2-5 last year in such situations would have given the team 9 wins. FO is careful to note that this may, however, be the result of terrible coaching (Ron Rivera).

Looking at the team’s statistical performance, the 2012 Panthers offense (Points Scored) was just 2% worse than average. Meanwhile, the teams was exactly average on defense. Put together, you’ve got the definition of an average team.

The biggest plus on offense is the assumed development of Cam Newton. Newton is entering just his 3rd year in the league and has obvious “elite” talent. While it’s reasonable to expect a player like this to improve, I do wonder how much “upside” is left. Cam Newton had an 86.2 QB rating last season, already a very strong performance. Additionally, compare the stat line from the last two years:

Notice anything?

The lines are close to identical. It’s possible that Cam Newton’s rookie year was actually a very good representation of his “true” ability. The biggest difference above is the significant decline in Interception Rate, which is obviously a big step forward (if it’s not a one year anomaly). However, the overall lack of improvement from year one to year two, combined with the fact that he’s ALREADY very good, tells me people might be overlooking the possibility that Cam is as good as he’s going to get (or at least close to it). In short, there’s not much higher he can go (and I don’t think he’ll ever challenge for the Brady/Manning/Rodgers level).

Before you ask, his rushing stats also show the same consistency from year one to year two.

On defense, the team returns a very strong DL backed by Luke Kuechly, who had an incredibly strong rookie year. The team, in the draft, added Star Lotulelei. Readers who followed my draft projections will know that Star ranked, according to the TPR system, as one of the biggest “steals” in the first round. If he is as good as those projections suggest, the Carolina defense will be strong (certainly stronger than last year).

The biggest issue is the Secondary, which was/is terrible. However, since the team managed league-average status last year with a similar group, I don’t see that costing them more this year. If anything, the stout front 7 should allow the team to scheme around its issues (a bit).

There aren’t a statistics that immediately jump out to me as “mean-regressors”, so not much adjustment to do there. The 2012 schedule strength wasn’t out of whack, so no potential there either.

Overall, I’m leaning more towards Bovada here than FO. All things considered, I’d put the Panthers at 8 wins, which is still higher than the Bovada line.

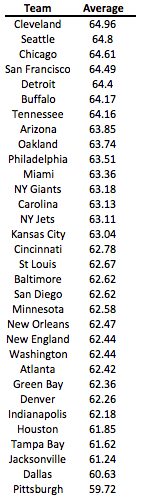

Washington

The Redskins are the other team that qualifies as significantly underrated, according to our comparison. FO projects the team to register 10.3 wins, which is 1.8 games higher than the Bovada O/U. Putting that projection in context, 10.3 wins is the 3rd HIGHEST FO projection (behind New England and Green Bay), tied with Denver and Seattle.

Raise your hands if you had the Redskins as a member of the “SB favorites” group.

Essentially, the FO argument for the Redskins is: RG3 is awesome. It’s a very valid point. a healthy RG3 and an average defense may be good enough to get you to 10 wins (it’s easily good enough for playoff contention). That’s the upside to having a Superstar QB.

Once again, I have to raise a few red flags regarding the FO projection.

– The 2012 Redskins had a TO differential of +17. Needless to say, that’s unlikely to repeat. In my database (last ten years) I can find just ONE team that registered a TO differential of +17 and managed to avoid a significant decline the next season, the 2011 Patriots (+17 followed by +25 last year).

– Despite having the league’s top rushing attack, the Redskins lost just 6 fumbles last year, with an overall recovery rate of 67%. Again, neither measure is likely to be as beneficial this season.

On the plus side for the team (minus if you’re an Eagles fan) is the recovery of Brian Orakpo, who missed most of last season with a pectoral tear. The defense was -7% last season in points scored, and adding Orakpo is a pretty big addition. Assuming the Redskins finish 2013 around the 0% mark on defense, the team merely needs to duplicate last season’s offensive performance to finish in the +70 to +80 point differential range.

That puts the team at around the 10 win mark (Pythagorean using a 2.67 exponent). However, given the TO stats I mentioned above, I think that’s the HIGH end of the potential range.

That’s slightly below the FO projection (10.3), meaning even if things go well luck-wise for the Redskins, I don’t expect the team to hit that mark (though 10 wins is essentially equal).

Regardless, Washington is likely to the best team in the NFC East, meaning Eagles fans need to pay attention. However, I’d say 9 wins is much more likely. Similar to the Carolina projections above, that leaves me in between the Bovada and FO lines.

Naturally, I just realized that we should take the average of the two measures to create a separate projection, so I’ll include that tomorrow, when we take a look at the most OVERRATED teams.