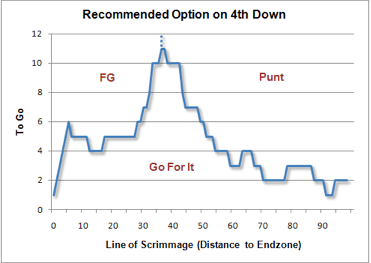

If you missed part one (posted yesterday), I encourage you to read it before moving to today’s continuation. At the end of yesterday’s post, we arrived at a default 4th Down Strategy chart, essentially a cheat sheet that tells coaches when to go for it and when to punt/kick a FG. For future reference, I have added the chart as a permanent fixture that can be accessed through one of the menu tabs at the top of the site. That should make watching the games more fun (or frustrating since you’ll know in real-time when bad decisions are being made).

Today, we move to grading. Using that chart, how do NFL Coaches perform? As I mentioned yesterday, this research was done by Jared Cohen, you can follow him on twitter at @jaredscohen.

Fair warning, this is a very detailed analysis (more of a research project) and therefore is longer than the typical blog post. Please read it when you have some time. If that’s not possible, feel free to skip to the charts.

Part 2

Methodology

To examine 4th down coaching decisions, I took the following steps.

- Download a comprehensive set of all fourth down plays from the 2012 regular season, including a set of key variables I could track and control for, including:

- Distance to go for a first down/touchdown

- Quarter and clock time of the play (e.g., Q1, 14:30)

- Field position (e.g., own 35 yard line)

- Scoring margin (e.g., team up by 3 points)

- Each play was segmented by the choice of its coach as either a punt, FG attempt, or conversion attempt (by rush or pass)

- Based on the distance for conversion and field position, I compared the fourth down play call to the optimal strategy matrix (the strategy card), to see what the ‘right’ choice would be

- A play call in which the coach made the optimal decision was termed a ‘Pass’, while a play call that was not (e.g., punting instead of aiming to convert 4th down) was termed a ‘Fail’

Pretty simple right?

Now, before getting to any data, I should also note that I excluded a number of specific plays, for reasons which I’ll explain. Remember, the goal of the analysis is to determine whether coaching decisions are optimal under normal circumstances. The key word here is normal.

– If a team was either leading or trailing by more than 14 points (two touchdowns), we excluded the decisions, reasoning that coaches would be making decisions differently than normal behavior (e.g., trying to catch up)

– If the distance required was longer than 10 yards (e.g., 4th and 12 yards to go), I excluded it. I did this largely because those situations usually aren’t decisions for the coach. It’s a pretty clear field goal attempt or punt depending on where you are, and my major area of focus was on situations where a coach could decide to go for it

– Plays were also excluded if they occurred in the last 2 minutes of the 2nd quarter or the last 5 minutes of the 4th quarter, as coaching behavior will also change significantly. In the 2nd quarter, it’s because a team can’t maintain possession. In the 4th quarter, it’s because the game is ending and teams will no longer be trying to maximize their total points, they’ll be more focused on gaining/maintaining a lead.

So while the aforementioned decisions could be interesting, they were in situations which are inherently not-normal. The main goal is to see what coaches do in a typical situation. Even after subtracting all these conditions, we have over 2,100 fourth down calls to evaluate. That should be plenty.

So what did we see?

Results

We saw a pretty large number of failures. I’d never want to play blackjack with these guys.

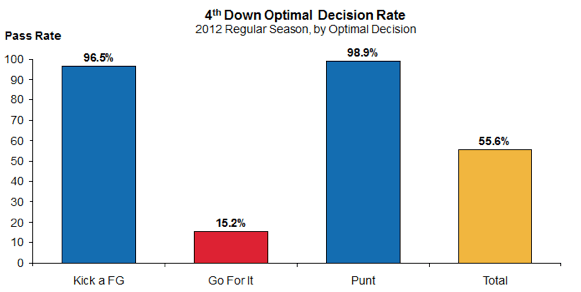

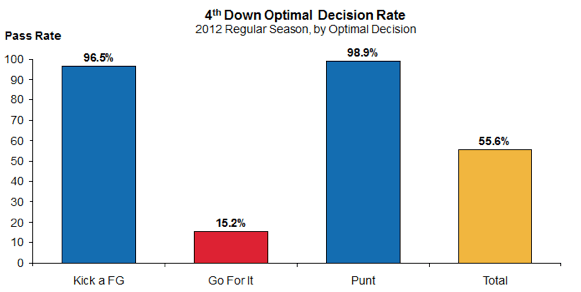

Below is a chart of the overall grade for NFL coaches’ fourth down decisions, by quarter.

Yes, you’re reading that right. When making a decision as to what to do on 4th down, the NFL coaching body as a whole makes the ‘optimal’ decision just slightly over half the time.

Think about that for a minute. In just about half of all normal 4th down situations, coaches are making decisions that fail to maximize their number of expected points (and we should expect, actual points).

That seems kind of strange. And yet it also seems completely believable in a league where principally ALL coaches are far too conservative.

But if we spend some more time peeling back this coaching decision onion, we’ll look at a couple more specific cuts of the data that can give us more insight on exactly where these decisions are happening.

This will include:

– Decisions by optimal decision (what kinds of decisions are the most frequently screwed up)

– Decisions by field position (how do decisions vary by where you are on the field)

– Decisions by yards to go (does optimal decision-making vary by distance)

– Decisions by coach (which coaches appear to have the highest grades)

– Decisions by scoring differential (does decision-making change when you’re ahead/behind)

– Some fun with coaches (looking at specific game decisions to understand exactly what the implications are)

But before we get to that, there are a few caveats to all this analysis, which I want to make clear. This is to head off complaints and anti-analytics folks who may have already commented about how I live in my mom’s basement.

- This analysis accepts the illustrated decision matrix as optimal, when in reality, that may not hold completely. It’s based on my interpretation of Brian Burke’s work, which I think is logical and is the leading model that I’ve seen. (I also ran these numbers with an alternative model generated for college football, and the results were consistent with expectations, which means they were much worse as college teams should kick field goals much less frequently than NFL teams do, hash marks and lower kicking talent level etc.)

- These optimal decisions do not take into account the talent/performance of the teams in question. It assumes equal teams are playing each other. So could a team with a great offense merit different ‘optimal’ choices where they go for it more often? Of course. You could also adjust for the defense of your opponent, the skill of your kickers, the opposing punt return man, home field advantage, weather, or any recent lunar eclipse. This doesn’t have any of those adjustments.

- When we get into very granular cuts of data (specifically with coaches), we start to run into potential sample size issues.

All of this is to say that yes, there are concerns with this (or any) piece of analysis. The goal of this isn’t to find incontrovertible proof, or establish new football dogma, it’s to investigate an issue and understand potential implications.

Analytics can serve as a helpful guide and show you where some issues might be, but I’m not going to pretend the conclusions are absolute.

Decisions by decisions (From the Department of Redundancy Department)

One of the reasons I wanted to look into 4th downs at all was because I’m continually frustrated by coaches kicking field goals or punting.

Coaches are too conservative, just about any research in football has suggested as such, and so when I put this sample together, I wanted to see what my data looked like.

The first thing I did was filter all the fourth downs based on what the ‘optimal decision’ actually was. Remember, each fourth down, based on our strategy chart, was either ‘Go for it,’ ‘Field Goal,’ or ‘Punt’, based on the action that would maximize your expected points.

So, if we sort our data by what the optimal decision should be, we can see whether NFL coaches are screwing up opportunities to punt, kick field goals, or go for it (hint – my money is on go for it)

As TMQ’s Gregg Easterbrook would exclaim, ‘Ye gods!’

The good news for NFL coaches, is that when they’re supposed to be conservative, they are fantastic about it. In situations where coaches should be kicking a field goal or punting, they decide to do just that 97% and 99% of the time, respectively. Amazingly optimal performance!

Of course, such high rates would suggest that our coaches are being extremely conservative, which probably seeps over into fourth downs where they should be trying to convert. And sure enough, the abysmal 15% pass rate on fourth downs where teams should be going for it is exactly what we’d expect to see from overly conservative managers.

That means that, when faced with a fourth down where the best outcome is to go for it, coaches choose to kick away (punt or FG) about 85% of the time.

Wow. That seems insanely high. Making the wrong choice 85% of the time? I feel like in most jobs those kinds of choices get you fired. If you make 85% of the burgers wrong at McDonald’s, you’ll most definitely be out of a job.

But to give you a sense of what these failing decisions actually look like, I’ve included a sample from my data set below:

All of these are example ‘fails’ by NFL coaches when the best choice would be to go for a first down. Some of them seem pretty obvious. Pete Carroll and the Seahawks had 4th and 2 from the Arizona 9 yard line and elected to kick a field goal (which by the way, they missed). Some of them, like Dennis Allen opting for a FG from the Chargers 33 on 4th and 6, seem a bit more arguable.

But across all those possible decisions, only 15% of them were the ‘optimal’ choice. Even with my earlier caveats (not adjusted for team ability or game situation), that still seems like something is systematically wrong with NFL coaches.

Decisions by Field Position

So we know what type of decisions coaches mess up. They’re too conservative and should be going for it more often.

But let’s keep going, and ask ourselves, are these decisions happening all over the field? Are they happening more in some areas than others?

I broke down the field into four main zones, and looked at the data that way.

- Own territory – Anywhere between your goal line and the 50 yard line

- The ‘Maroon Zone’ – A term I borrowed as an homage to TMQ, who has consistently railed on over-conservative coaching for years. My definition of the Maroon Zone is in opposing territory, but not as far as the opposing 35 yard line. Too far for a field goal, but surely too close to punt!

- FG Range – Any position between the opposing 35 yard line and the opposing 20 yard line. From the 35 yard line a field goal would be 52 yards, which is more or less the regular range of today’s NFL kickers. We could split hairs and more it back a few more yards, but this was where I decided to draw the line.

- Red Zone – Anywhere from the opposing 20 yard line to the opposing goal line

So I set these bins and filtered the fourth downs. Where on the field are teams making more suboptimal decisions?

I should’ve saved the ‘Ye Gods’ for this, huh?

One of the first things that jumps out is that coaches make the most optimal decisions in their own territory. This makes sense, as we know our coaches are big on punting, and in their own territory, that’s more likely the right decision. (Of course, in an absolute sense, getting only two-thirds of decisions right isn’t exactly fantastic)

The other thing that jumps out is the performance in the Maroon Zone, so opposing territory but a bit too far for most field goals. Coaches are only making the right decision about 32% of the time here.

Again, some of you might be wondering types of decisions this entails, so I’ve pulled a sampling of Maroon Zone decisions. This table illustrates eight examples of Maroon Zone decisions from my data set, all from the first quarter of the first week of this season. It includes the coach, matchup, down and distance, score position, decision (both actual and optimal), and grade.

Let’s take the first row, when Mike Munchak and the Titans, facing a fourth and 1 from the opposing 37 yard line, faced a decision. You’ll see the Titans elected to pass, and that the optimal decision was to go for it. For that ‘passing’ decision, they received a ‘1’ grade.

Contrast that with Mike McCarthy and the Packers in their game against the 49ers. McCarthy had a decision on fourth and 3 from the 49ers 45 yard line. At the time, the Packers were down three points. With arguably the best quarterback in football and a stable of talented receivers, did McCarthy choose to go for it?

No, the Packers punted. Now, you could argue that the 49ers have a great defense and field position is key and blah blah blah. I’m not saying those arguments have no merit, I’m just saying I would’ve gone for it, and in that situation, going for it is the right move.

You may ask what happened on those plays? What were the outcomes? Did the Titans convert the first down? Did the Packers punt give them great field position?

Well, frankly, I don’t care what happened. Judging a decision based on the outcomes creates a whole set of biases which I don’t want to influence our analysis. The goal of this is to understand whether coaches are making the right decisions, not whether those decisions ended up working out. To me, that means we should keep the outcomes completely outside of this conversation.

Decisions by Yards to Go

So coaches aren’t going for it enough, and although they make the wrong decision most of the time whenever they’re in opposing territory, it’s at its worst when they’re beyond field goal range.

That’s interesting, if not completely unexpected.

But how is their decision-making impacted by the distance required for a first down? Is there any difference to a coach’s decision making whether its 8 yards to go vs. 3 yards to go?

Again, not a shocking result.

When the optimal decision is a more conservative approach (like punting on a fourth and ten), coaches almost always get it right.

But as the distance to convert shrinks, performance gets remarkably worse, especially around 2-3 yards to go, when coaches are only getting it right one-fifth of the time.

Again, it’s the conservative approach that does them in. When coaches should be trying for conversions, they’re punting the ball away or attempting a field goal. What’s interesting is that with only one yard to go, they’re actually a bit better. I feel like it’s a gap based on aesthetics more than anything else. One measly yard? We can go get that! The coach may say to himself. But push it back another three feet and it somehow becomes impossible.

Now we’ve seen just how bad NFL coaches (as a group) are when it comes to optimal 4th down decision-making. Tomorrow, we’ll look at individual coaches to see who is the best (or least bad as the case may be). The results are shocking…