NOTE: This post got away from me a bit. It’s a long one (1200+ words). If you’re short on time, read the first section covering the 2012 Eagles, then skip to the very end to see the conclusions for today.

So yesterday I showed that Total Fumble Recovery Rates are both random and Normally distributed. The takeaway was that there is a 97.5% chance that the Eagles will recover fumbles next season at a higher rate than they did this season.

That’s important, since it will almost definitely be a push in the positive direction for the team. However, it’s far from the whole story.

There are a couple more aspects to cover. I told you yesterday that we would take a look at recovery rates broken down by giveaways and takeaways, so I’ll do that first. Then I’ll take a look at the more interesting question: Is Forcing Fumbles the result of luck or skill? Feel free to skip to the end if that holds more interest for you.

Giveaway/Takeaway Recovery %

Not all fumbles are created equal. For starters, see this article. In general, it shows that recovery rates differ by TYPE of fumble. For example, an offense is much more likely to recover a dropped snap than fumble by a receiver. I won’t go into that much detail here; the linked article is worth a read for anyone interested. Let’s take a look at the higher level stats though (Source: Teamrankings.com).

The long term NFL average recovery rate for “giveaway” fumbles is 52.31%. That means that an offense, on average, recovers 52.31% of the fumbles it commits.

Conversely, a defense recovers, on average, 47.48% of the fumbles the OPPOSING offense commits.

Note that those two numbers do not add to exactly 100%, which I assume is due to fumbles that go out of bounds and are therefore recovered by neither team.

So what happened to the 2012 Eagles?

The Eagles, last season, recovered just 40.5% of the fumbles they committed. That is roughly 12% below the expected recovery rate. That’s bad. However, it’s hardly a large enough deviation from the average to explain the overall performance. So…

The Eagles, last season, recovered just 25% of the fumbles the other team committed. That is more than 22% below the expected recovery rate, a huge deviation. In fact, over the past 10 years, only 4 teams have recovered opposing fumbles at a lower rate. Previously, I highlighted that the Eagles only “gained” 5 turnovers on fumbles last season, FAR below the long-term league average of 11. However, the team (according to ESPN) forced 17 fumbles, almost equal to the NFL long-term average of 17.15.

So the 2012 Eagles actually forced fumbles at a league average rate, but recovered them an extremely low percentage of the time (which is luck). That is also extremely unlikely to happen again next year.

Is Forcing Fumbles Luck or Skill?

Now we’re getting to the more interesting stuff. Recovering fumbles appears to be ENTIRELY luck. However, if forcing fumbles is the result of skill, then teams have some control over the Fumble Differential equation. So how do we know?

Similar to yesterday, we can’t know for sure without an extremely in-depth study and a lot more computing power than I have. However, let’s look at a few different areas to get a good idea of what’s happening.

First up is team persistence. If forcing fumbles is the result of skill, then we can expect teams that are “good” at it to continue being good at it year after year. If it is a skill, then it is repeatable.

Here is the chart for forced fumbles, the axes are Year X and Year X+1.

Doesn’t look like much. The correlation value is .083, which is very small (obviously).

Just in case a year-to-year look was too susceptible to short-term variability, I also looked at the correlation between the 2-yr average and the following seasons total for each team. Again, a value of .087, still very weak.

That’s certainly a strike against skill, but we’re not finished.

What about individual players?

We all remember watching Charles Tillman last year (he forced 10 fumbles). Based on just last season, it seems like it’s safe to say he is actually “good” at forcing fumbles. If he is “good”, than it’s a small logical step to say that others must be good as well.

If forcing fumbles is a skill, then we should see the “best” fumble forcers towards the top of the leaderboard each year. Here is every player that forced 4 fumbles or more in a single season over the past 5 years. Click to enlarge. I’ve highlighted the players who appear on more than one list.

It appears as though there are some players who consistently force a high number of fumbles (relative to the rest of the league). However, notice the degree of variability in both the number of fumbles forced and the number of players who appear just once. Some of you will have already noted, though, that what we should really be looking for is RATE. Next week, I’ll try to equalize for that (thought of it too late for today’s post).

For now, I think it’s best to say that at an individual level, certain players appear to force fumbles more often than others, meaning it may be the result of skill. However, given how many people are on the field at once, the relative impact of that player contribution may be small enough that it’s relatively insignificant to the overall game. Not there yet, I’ll try to detail this more next week.

What about teams?

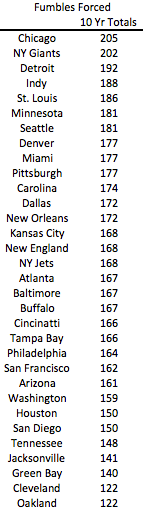

Certain teams appear to be better at forcing fumbles than others (the Bears are the obvious example). The Bears look as though they’ve made forcing fumbles a large point of emphasis. Looking at the overall totals from the last ten years bears this out.

The Eagles are close the middle of the pack, having forced 164 fumbles over the past ten seasons. The NFL Average is 166.9.

Does this mean the Bears are “better” at forcing fumbles than other teams? Maybe.

As I showed above, there is really no persistence in the year-to-year forced fumble data. However, the team totals data is Non-Normal and skewed negatively (meaning the distribution is thicker at the high-end than the low), as are the single season totals. Despite the persistence values, it appears as though, at the margins, some teams/players do create fumbles at a relatively high rate (have to confirm though).

Similar to yesterday, I have now provided more questions than answers. I will attempt to answer some of those next week. Allow me though, to sum up in as clear an explanation as possible:

“Creating” fumble turnovers is the result of two discrete factors.

– Forcing the fumble.

– Recovering the fumble.

How do the relative correlations of these two factors compare? In other words, to what degree is “fumbles gained” explained by each of these?

Here is Forcing Fumbles to Fumbles Gained:

The correlation value is .676, very strong.

Here is Recovery rate to Fumbles gained:

The correlation here is .59, also quite strong.

The difference in correlation strength is big enough to notice (.086), but relatively small.

Here’s the key part:

– The two factors (recovery rate and # forced) appear to be relatively equal in importance.

– Recovery rate is completely random.

– # of fumbles forced appears to be largely random (though skill is involved). This needs more work, but putting those two factors together means:

While there may be some individual skill involved in forcing fumbles, when incorporated into the whole “fumble equation”, that contribution is small, and certainly less of a factor than random chance (luck).

Congratulations if you’ve read this far. As is often the case, I ended up pretty far from where I intended to.